We treat GenAI like magic. But intelligence — real or synthetic — needs power, cooling, and infrastructure. What happens when that becomes ambient?

Thought Exploration Series

6 min read

August 21, 2025

We treat GenAI as frictionless — but every prompt draws on real infrastructure, with real cost.

And while the environmental impact of AI isn’t yet part of the public imagination the way flights, cars, or fast fashion are, that may be changing.

These systems are growing fast.

And their appetite is only beginning to register.

The Cost Behind the Curtain

Most conversations about AI and energy start with training. Yes, training GPT-3 consumed around 1,287 megawatt-hours — comparable to the annual energy use of hundreds of U.S. homes. But it’s the inference — the daily use, the answering of prompts like this one — that’s quietly taking center stage.

Each ChatGPT interaction consumes about 2.9 watt-hours of electricity — roughly ten times what a Google search uses, according to researcher Lennart Heim. It might not sound like much on its own, but with hundreds of millions of prompts per day, the cumulative load becomes significant.

To put that into context:

- Charging a phone once: ~8–10 Wh

- One hour of Netflix: ~400 Wh

- One cheeseburger (full footprint): ~3,100 Wh

No, it’s not the worst offender in your daily digital routine — but it’s no longer negligible.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that GenAI now accounts for 5–15% of total electricity use by data centers worldwide. That’s worth unpacking.

Data centers are the backbone of the internet — rows of servers running everything from search engines to banking apps. In 2023, those centers consumed roughly 415 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity — around 1.5% of global electricity demand. So when GenAI eats up even 10% of that, we’re talking over 40 TWh annually — just to keep synthetic intelligence humming.

And this growth is happening fast. It took decades for the internet’s core infrastructure to reach that kind of scale. GenAI could reach 20–40% of total data center energy use by 2030, in less than a decade. That curve isn’t linear. It’s exponential. And it places massive pressure not just on chips or code — but on the energy grid beneath it all.

. . . . .

Cooling Thought

And then… there’s water.

Not metaphorical water. Literal, physical water.

Because AI is hot. Computationally hot. And it needs cooling.

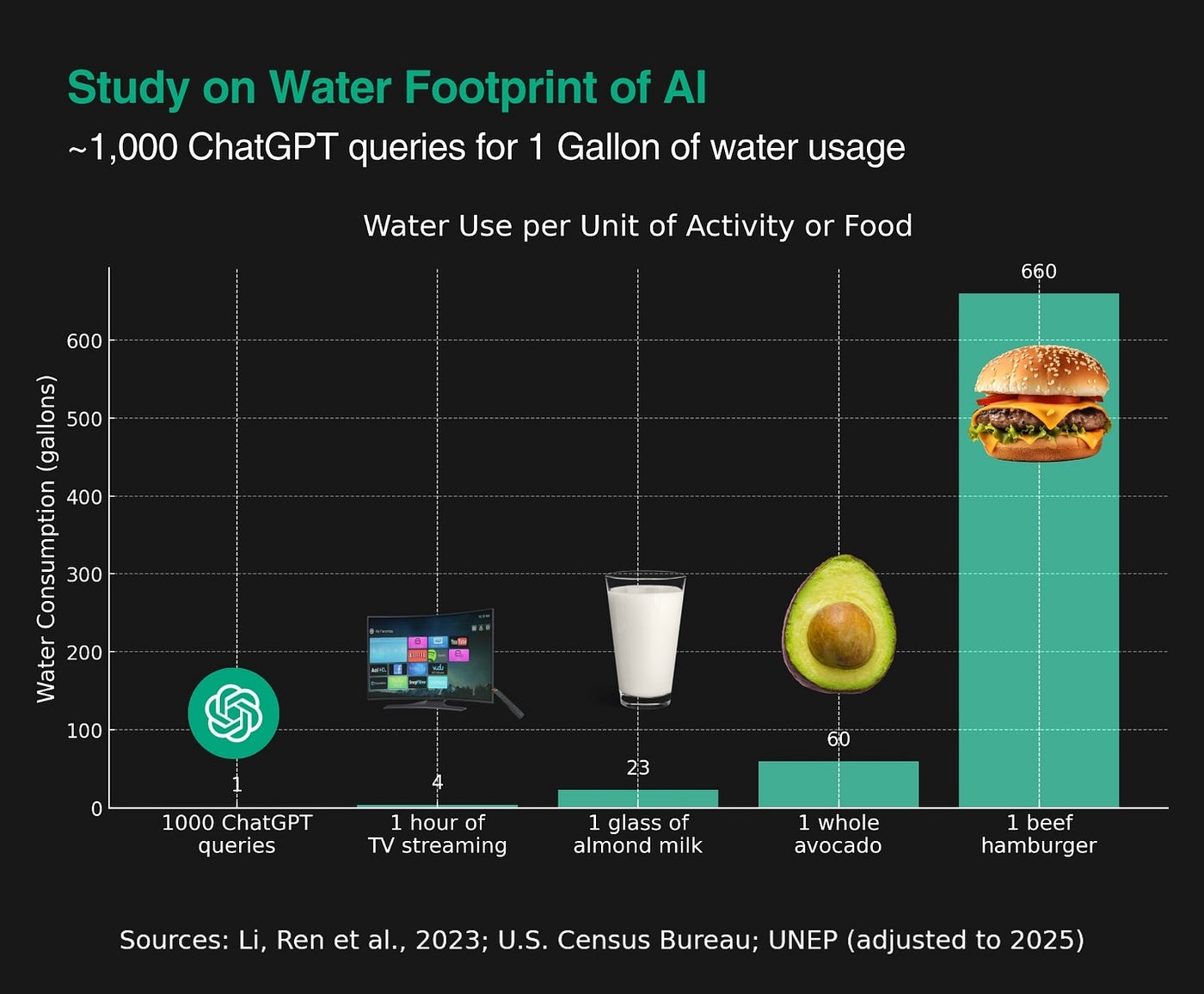

High-performance GPUs produce significant heat. To prevent failure, data centers rely on cooling systems — many of which use massive volumes of water to dissipate that heat. According to research from UC Riverside, each ChatGPT interaction may require around 500 milliliters of water just to cool the servers running that request.

That’s half a liter, per prompt.

Compare that to:

- Google search: ~50 ml

- Almond milk latte: ~74 liters

- One hamburger: ~2,500 liters

- One pair of jeans (lifecycle): ~7,500 liters

These numbers vary by region, season, and system — but the broader trend is clear: GenAI is adding a new kind of pressure on water systems already under strain. In places like the American Southwest, Northern China, and parts of the Middle East, water scarcity is real — and so are the tradeoffs between feeding server farms and feeding people.

This isn’t speculative. Some local governments have already delayed or denied data center permits due to water usage concerns.

The tension is quietly rising.

And it’s a reminder: the future won’t just be made of chips. It will be shaped by whether we can cool them.

. . . . .

Designing the Load Before We Understand the Weight

The hard truth is: we don’t really know where GenAI is headed.

It might replace energy-intensive processes — streamlining logistics, reducing travel, automating wasteful workflows. Or it might quietly ramp up demand, embedding always-on inference into every tab, slide, and call we make. Either way, the systems we’re building now will calcify into the infrastructure we’ll live with later.

We’re not just scaling intelligence. We’re scaling the energy architecture that supports it. And we’re doing it before we’ve built the frameworks to measure what’s actually being gained — or lost.

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

— Roy Amara

So this isn’t just about forecasting — it’s about design. We need to stop thinking in single metrics and start thinking in energy ecosystems. A + / — model for GenAI’s footprint: where it replaces energy-intensive activity, where it adds new layers of consumption, and where it creates compounding overhead.

Where does inference displace human labor or avoid emissions?

Where does it simply shift the burden to another part of the stack — or another region’s grid?

We need better tools to surface those tradeoffs early. Not just carbon accounting after the fact, but dynamic energy mapping — so decisions aren’t made in the dark.

Because once the architecture hardens, so do the habits. And by then, it’s no longer just a design choice. It’s a structural dependency.

. . . . .

The Next Frontier Isn’t the Model. It’s the Grid.

A growing number of AI researchers working between U.S. and Chinese labs are starting to say it outright: the biggest bottleneck to GenAI isn’t talent or compute — it’s electricity.

In China, energy availability is centrally managed. Grid expansion is proactive, not reactive. Giant GPU clusters are deployed with massive state support, and infrastructure is scaled to match. In the U.S., by contrast, the electric grid is becoming the primary constraint. Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are delaying or cancelling new data center builds in regions where the grid simply can’t handle more demand.

In this next phase, power availability may become more important than model architecture.

And that shifts the stakes entirely.

If GenAI’s future is gated not by innovation — but by infrastructure — then the most important question isn’t “What can it do?”

It’s: “Where can it run?”

. . . . .

Sources & References

- Heim, L. (2023). How much does ChatGPT cost OpenAI?

https://www.lennartheim.com/p/how-much-does-chatgpt-cost-openai - Li, S., Ren, X., et al. (2023). Making AI Less “Thirsty”: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03271 - International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Electricity 2024 — Analysis and forecast to 2026.

https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2024 - International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Energy Demand from Artificial Intelligence.

https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai - Water Footprint Network. Product Gallery — Global Average Water Footprint.

https://waterfootprint.org/en/resources/interactive-tools/product-gallery - NRDC / Stanford. (2020). The Climate Cost of a Cheeseburger.

https://www.nrdc.org/resources/eat-your-way-cleaner-environment - Strubell, E., Ganesh, A., & McCallum, A. (2019). Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.02243 - Fortune (2025). Data centers and the China energy edge.

https://fortune.com/2025/08/14/data-centers-china-grid-us-infrastructure

. . . . .