Quantum computing isn’t just faster. It’s a different way of thinking about logic, uncertainty, and what it means to compute.

Thought Exploration Series

7 min read

August 6, 2025

For decades, we’ve ridden the exponential wave of Moore’s Law — the idea that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years, making our computers faster, smaller, and cheaper with each generation.

But we’re hitting a wall.

Transistors are now just a few atoms wide. We can’t shrink much further without running into quantum effects — unpredictable behaviors like tunneling or superposition that emerge at atomic scales and disrupt the clean on/off logic of classical circuits.

Ironically, those same effects that break the old system may now be the foundation of a new one.

This is where quantum computing enters — not as an upgrade to our existing systems, but as a completely new way of thinking.

“The next big frontier is not just better computing, but different computing.” — David Deutsch

Why Quantum Is Different

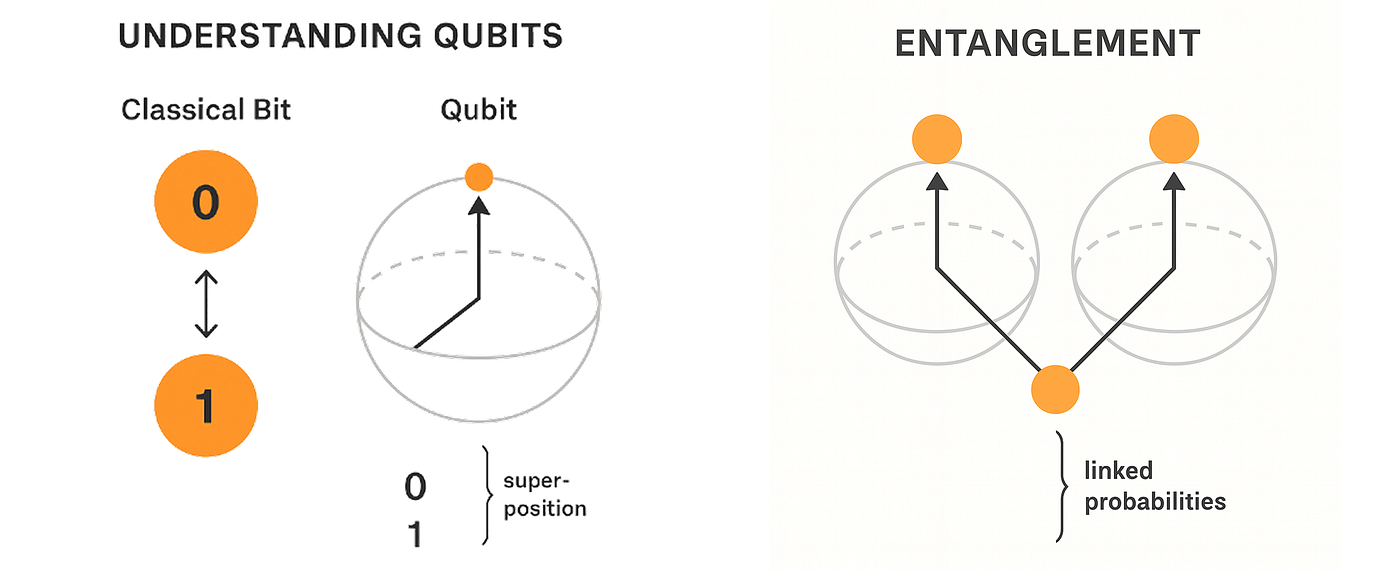

Classical computers are built on bits: tiny switches that are either on (1) or off (0). Every task — from streaming a movie to calculating a rocket trajectory — is performed by processing long sequences of these bits using logic.

Quantum computers are built on qubits, which can be in a state of 0, 1, or both at once. This is called superposition.

Think of a bit as a coin lying flat — either heads or tails. A qubit is like a coin that’s spinning in the air, containing the potential for both, until the moment you catch it.

This allows quantum systems to process many possibilities at once. When multiple qubits are entangled, their outcomes are linked — so that even when separated by distance, the state of one instantly affects the other. It’s not magic. It’s a physical property of the quantum world.

Together, superposition and entanglement allow quantum computers to solve certain classes of problems that classical computers can’t touch — not because they’re slower, but because they’re limited by the sequential nature of binary logic.

Take molecular modeling as an example. Even the simplest molecules involve complex interactions between electrons, which classical computers must simulate step by step — an approach that scales poorly and quickly becomes impossible. A quantum computer, on the other hand, can model these quantum interactions natively, because it operates by the same rules. It doesn’t just simulate the system — it becomes one.

“If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” — Richard Feynman

So… What Exactly Is a Qubit?

Let’s get very specific.

A qubit (short for quantum bit) is the basic unit of quantum information. It behaves according to the rules of quantum mechanics, not classical physics. Unlike a regular bit, which is always either 0 or 1, a qubit can exist in a blend of both states at the same time — until measured.

But a qubit isn’t just an idea. It must be physically embodied in a system that naturally exhibits quantum behavior.

What Is a Qubit Made Of?

There are multiple physical systems scientists use to create and control qubits:

- Superconducting Qubits: Tiny loops of superconducting metal, cooled to near absolute zero. Used by IBM and Google.

- Trapped Ion Qubits: Individual atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields and manipulated with lasers. Used by IonQ and Honeywell.

- Photonic Qubits: Single particles of light, with their orientation or phase encoding quantum states.

- Spin Qubits: Based on the spin direction (up/down) of an electron or atomic nucleus, controlled by magnetic resonance.

Each has trade-offs — some are more stable, others more scalable — but they all share a core challenge: qubits are extremely fragile. Any heat, vibration, or interference can cause a qubit to lose its quantum state, a problem known as decoherence. That’s why most quantum systems operate in ultra-cold, ultra-controlled environments.

From Quantum Weirdness to Actual Computation

Here’s the big question:

How do we turn all that strange quantum behavior into something useful?

The process looks like this:

- Prepare the qubits in superposition using lasers, microwaves, or magnetic fields.

- Entangle and manipulate them using quantum gates — specialized instructions that determine how qubits influence each other.

- Measure the result — which collapses the system into a specific set of values: a result that a classical system can read and interpret.

You don’t observe every possibility. Instead, you design the algorithm to amplify the probability of correct outcomes and suppress the wrong ones — so when the system collapses, it’s most likely to give you the answer you want.

Quantum computers don’t walk down a path. They explore many paths simultaneously, and you shape the landscape so that the correct answer becomes the most natural place to land.

“Quantum hardware is not built. It is stabilized.” — Seth Lloyd

Where We Are Now

Quantum computers already exist — but they’re still early-stage. Most of today’s machines fall into the category of NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) — limited in size, error-prone, but already proving useful in narrow tasks like modeling molecules or simulating certain materials.

Companies like IBM, Google, PsiQuantum, and Quantinuum are racing to build more stable, scalable systems. Governments are investing billions. Breakthroughs are happening — but quietly, in labs and research centers, not on store shelves.

We’re probably 5–10 years away from fault-tolerant, general-purpose quantum systems.

And no, they won’t replace your laptop.

They’ll exist in highly specialized environments, solving complex problems that classical machines simply can’t process — whether in chemistry, logistics, finance, or encryption.

A Different Kind of Mind

Perhaps the biggest shift quantum brings isn’t technical — it’s conceptual. Classical computers mirror a certain worldview: step-by-step reasoning, binary logic, predictable outcomes. They’re machines built to follow instructions in a clean, traceable order.

Quantum systems defy that structure. They don’t compute by following a path; they operate in a space where possibilities coexist, influence each other, and only resolve into outcomes when observed. This isn’t randomness — it’s structured uncertainty. A quantum computer explores a field of probabilities, and through careful design, we influence how that field collapses into something useful.

That’s more than a new kind of processing. It’s a different framework for understanding problem-solving altogether. In the quantum paradigm, information doesn’t flow — it hovers, interacts, entangles. Computation becomes less about following logic and more about shaping conditions from which insight can emerge.

This challenges our assumptions — not just about technology, but about knowledge, decision-making, and intelligence itself. If we embrace machines that don’t follow our logic, we may also need to reimagine how we define clarity, certainty, and control.

“The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.” — Niels Bohr

So What Happens When It Works?

Quantum systems won’t just make existing tasks faster. They’ll let us tackle problems that are currently beyond reach — simulating new materials before we synthesize them, designing drugs before we test them, optimizing global systems too complex for current models.

But they’ll also reshape how we relate to knowledge. If our machines are built to work with ambiguity rather than eliminate it, we’ll need to get more comfortable with ambiguity too.

We’ve spent decades teaching computers to follow our logic. Quantum computing is a quiet, radical invitation to meet a logic that isn’t ours — and learn to work with it.

Sources & Further Reading

- IBM Quantum. “What is quantum computing?”

A clear introduction from one of the leading companies building real quantum machines. - Google AI Blog. “Quantum Supremacy Using a Programmable Superconducting Processor.”

Google’s 2019 paper on achieving quantum supremacy, with practical implications. - David Deutsch, The Fabric of Reality

A philosophical and technical exploration of quantum theory’s implications on knowledge and computation. - Scott Aaronson, “Quantum Computing Since Democritus”

A deep but accessible collection of lectures on the theory and paradoxes of quantum computation. - Seth Lloyd, Programming the Universe

A bold take on the idea that the universe itself might be a quantum computer. - Qiskit Textbook by IBM. Learn Quantum Computation using Qiskit

An open-access resource for hands-on learning about quantum programming and theory. - MIT Technology Review. “Quantum computing is coming. What can it do?”

A realistic breakdown of what quantum computing can (and can’t) do today.

. . . . .