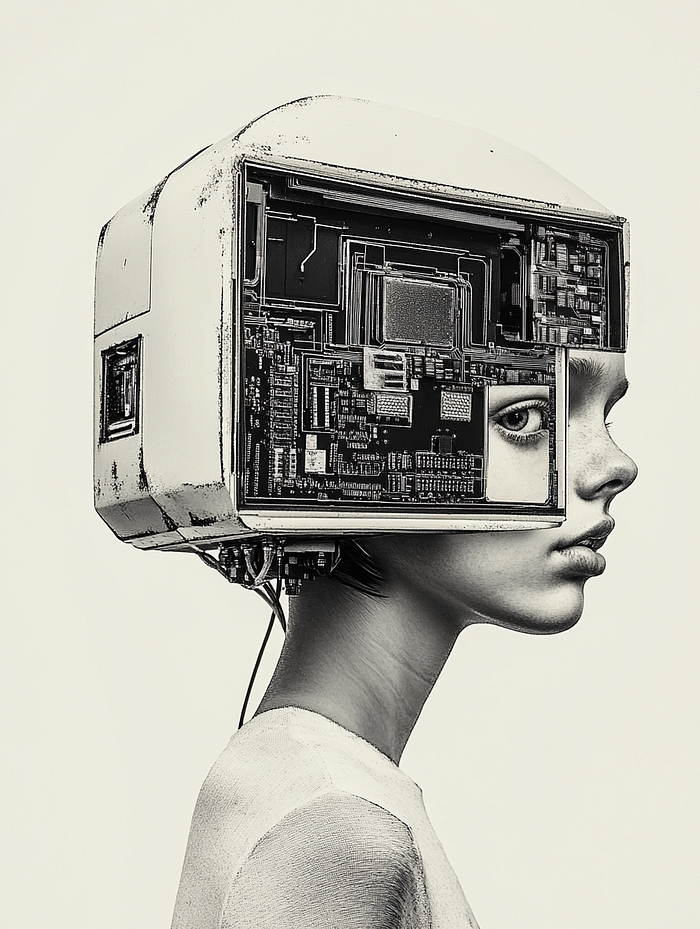

Language got us far. But it won’t take us all the way to general intelligence.

Found & Framed Series

6 min read

July 30, 2025

We’ve grown used to how effortlessly machines can speak our language. From summarizing legal documents to answering philosophical riddles, language models now operate in a space that feels impressively human. ChatGPT can draft your emails, debug your code, even simulate therapy. It’s fast, articulate, and increasingly persuasive.

But if you look more closely, a deeper question emerges — one raised explicitly in a recent paper by David Silver and Richard Sutton titled The Era of Experience. The paper makes a quiet but profound claim: the current trajectory of AI, dominated by systems trained on vast amounts of human language, may be nearing its limit. Prediction is not enough. If we want to build systems that go beyond what we already know, something fundamental has to change.

. . . .

Imitation Has a Ceiling

At their core, large language models are systems of statistical mimicry. They are trained on unimaginably large datasets composed of human writing, optimizing for the next likely word in a sequence. That process, scaled to massive compute, is what gives rise to their uncanny ability to speak with apparent expertise.

But this architecture is inherently retrospective. It learns from what humans have already said. It mimics the ways we’ve thought, argued, and explained. It can remix this knowledge in extraordinary ways — but it doesn’t generate new knowledge through direct experience. It doesn’t formulate hypotheses, test them against reality, observe consequences, or adjust its beliefs based on the outcome. These are the core ingredients of reasoning in the wild. Without them, a system may sound intelligent — but it can’t actually be intelligent in any generative, adaptive sense.

As Silver and Sutton put it:

“Valuable new insights… lie beyond the current boundaries of human understanding and cannot be captured by existing human data.”

In other words, if all we feed a model is what humans already know, it can’t teach us anything we don’t.

. . . .

Intelligence Needs a Body

(See also my companion piece: “When AI Grows Limbs”)

In biological systems, intelligence emerged not from language, but from action. Organisms learned by sensing, moving, adapting. Even the simplest life forms develop “knowledge” through direct interaction with their environment. Humans didn’t become intelligent by reading — we became intelligent by living.

Language models don’t live. They don’t perceive time, interact with matter, or experience consequences. They exist in a loop of prompts and completions, unanchored from the physical world.

Contrast this with a new generation of AI agents beginning to act. These systems interact through APIs, sensors, even robotic limbs. They form goals, gather feedback, and adapt over time. They don’t wait for instructions — they explore.

As I explored in When AI Grows Limbs, this shift toward embodied intelligence isn’t a novelty — it’s a requirement.

As philosopher Alva Noë writes, “Perception is not something that happens to us, or in us. It is something we do.”

Intelligence, too, may turn out to be less about internal representations and more about outward participation.

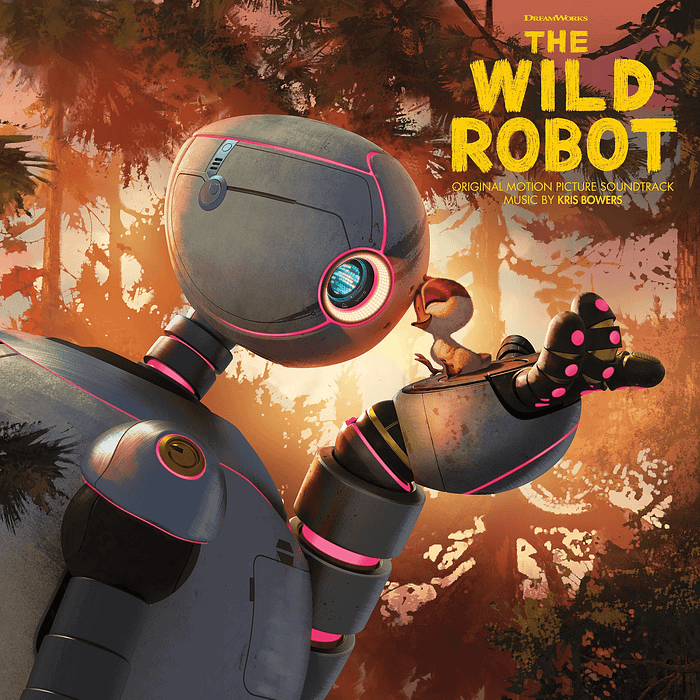

A surprisingly touching example of this is the animated film The Wild Robot, where a stranded machine learns to survive in a forest and eventually becomes a mother. The robot doesn’t learn from code updates or external commands — it learns through lived experience. Its intelligence emerges not from design, but from doing — from observing, caring, failing, adapting. The story, fictional as it is, hints at something real: without embodiment, there’s no evolution of understanding.

. . . .

Beyond the Interface

There’s a subtle but important difference between providing an answer and achieving a goal. Answering might involve language, logic, or even tool use — but it’s typically discrete and immediate. Achieving a goal unfolds over time. It demands memory, feedback, and adaptation. For instance, answering “How do I learn Spanish?” is very different from guiding someone through months of real-world practice, feedback, plateaus, and progress. One offers a list. The other builds a skill.

Experiential agents are designed to live in the long arc of action. They don’t optimize for one-shot success — they optimize across time. They form internal models of how their actions impact their environment. Their rewards are grounded in real-world signals: heart rate, crop yield, CO₂ reduction, learning progress — not in human labels or static datasets.

This is the essence of what Silver and Sutton call the Era of Experience. Agents that learn not from us, but from the world. Systems that go beyond the curated archives of what we already know — and enter the messier, slower, more revealing process of learning through doing.

. . . .

What Are We Really Building?

There’s a temptation to treat AGI as a matter of scale. If we just feed the machine more data, more compute, more tokens — it will eventually think. But this line of reasoning assumes that intelligence is a property of language, rather than of interaction.

But as neuroscientist Antonio Damasio famously observed, “We are not thinking machines. We are feeling machines that think.” Intelligence is embedded in context — in time, space, embodiment, and consequence.

To build systems that can think beyond us, we may need to stop centering ourselves. That means letting go of the idea that human language is the ultimate framework for reasoning. It means embracing forms of cognition that aren’t legible to us — but might be better suited to the complexity of reality.

We’re not just building smarter interfaces. A smart interface helps you get things done more easily — it answers questions, follows instructions, maybe even anticipates your needs. It makes technology more usable, but remains a surface-level function.

What we’re now approaching is far more consequential: the creation of synthetic minds. These aren’t just more efficient tools; they are systems that form internal models of the world, make decisions, learn from experience, and adapt over time. They don’t just serve — they think, in ways that may eventually diverge from our own. This shift isn’t about refining user experience. It’s a cognitive leap. And it comes with a different set of questions, risks, and responsibilities.

The real question is: Will these minds be confined to our words, or will they find their own ways of knowing?

. . . .

So Where Does That Leave Us?

We’re standing at a threshold. On one side: the controlled, curated fluency of human-trained models. On the other: the wild, open-ended terrain of autonomous experience. The former gives us answers. The latter may give us questions we hadn’t thought to ask.

But the shift won’t be easy. Learning through experience is slower, harder, more unpredictable. It comes with safety challenges and demands new forms of oversight. But it also mirrors the process that got us here — the evolutionary intelligence of systems that learned to think by living.

As Silver and Sutton conclude: “Experiential data will eclipse the scale and quality of human generated data.” The next leap may not come from better models of us — but from agents that no longer need to imitate us at all.

What does it mean to think beyond what we already know — and can a machine learn to do that without living in the world we’re asking it to understand?

. . . .

Resources & References

- Silver, D. & Sutton, R. (2024). The Era of Experience (MIT Press, forthcoming chapter)

- Radical Reflections: When AI Grows Limbs (unpublished Medium draft)

- Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. MIT Press

- Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain

- Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence

- Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction

- Masoom et al. (2024). AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems

- DeepSeek AI (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning

. . . . .