The rise of physical intelligence — and the slow redefinition of what it means to have a body.

Thought Exploration Series

6 min read

June 24, 2025

All media are extensions of some human faculty — psychic or physical.”

— Marshall McLuhan, media theorist

We’ve gotten used to thinking of AI as something disembodied. A brain in the cloud. A pattern-recognition engine behind a screen. It answers questions, generates content, maybe even writes your emails — but it doesn’t move through the world the way we do.

But that assumption is beginning to crack.

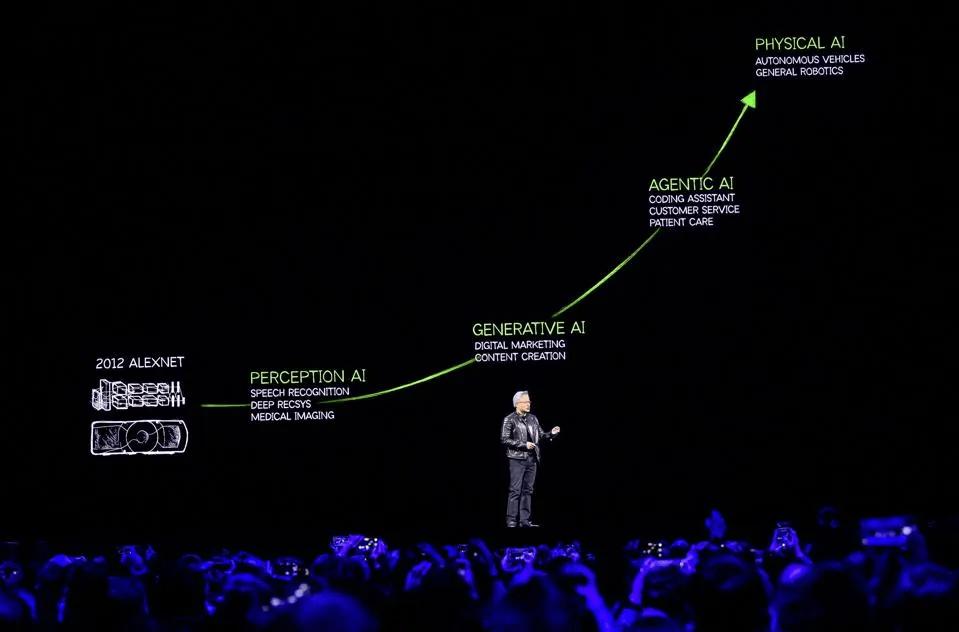

Earlier this year, Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang called physical AI the next frontier. Not smarter chatbots. Not better prompts. But intelligence with agency in the physical world — robots, limbs, machines that can perceive, decide, and act. AI that doesn’t just compute, but acts in the world — lifting, grasping, navigating, manipulating objects. Intelligence that doesn’t stay on the screen, but moves through space.

It’s a shift that collapses the divide between thought and movement. And more importantly, it’s a shift that reopens an old question:

What does it actually mean to have a body?

“The next wave of AI is physical. Robots that understand the world, interact with it, and adapt in real time.”

— Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia. . . . .

Intelligence, now with arms

The body was once considered the limit of self — our boundary and our baseline. But today, that boundary is more porous than we admit.

In Tokyo, a research team has created Jizai Arms, a wearable platform that allows users to control up to six robotic limbs. They can be detached, swapped, even shared between users. These aren’t prosthetics. They’re augmentations. Additional capacity, not replacements. Tools that behave like extensions of your will.

And crucially, these limbs don’t have to be physically attached. They can be in another room. Or another country. Controlled remotely via neural signals or digital interfaces, they allow a person to act at a distance — to move something without being near it, to participate in environments they never enter. The implications stretch far beyond assistive tech. This is distributed embodiment. You could have a limb in Tokyo, another in Nairobi, all acting on your behalf. The idea of “presence” starts to fragment.

At MIT, researchers are developing supernumerary robotic limbs — mechanical arms that assist workers by holding tools, supporting weight, or acting as third and fourth hands. The goal isn’t to correct disability. It’s to enhance performance. Functionality, multiplied.

In both cases, AI isn’t just making decisions — it’s making contact. It’s responding to context in real time, coordinating with the user’s movement, and adapting its behavior to the task at hand. This is embodied intelligence. Reactive, relational, and increasingly autonomous.

We are beginning to co-habit with machines that share our intentions and extend our reach — not just metaphorically, but literally.

And it raises a new kind of question:

When we operate through machines that aren’t technically “us,” how far does the self extend?

. . . . .

Hacking evolution, one limb at a time

For centuries, the body evolved under strict constraints. Two arms. Two legs. A narrow margin for error. The cost of change was high, and time did the editing.

But we’re no longer playing by those rules. We’re designing tools that exceed the assumptions of biology — and strapping them on like accessories.

“Technology is a cosmic force. We are not just using it — we are becoming it.”

— Kevin Kelly, founding editor of WIRED

This isn’t speculative anymore. It’s consumer-adjacent. Open Bionics already produces the Hero Arm, a stylish prosthetic with modular components and precise control. What used to be a marker of loss is now a site of design and pride.

And it doesn’t stop with function. Some researchers are going deeper — into organic robotics. These are soft machines, often built with bio-compatible materials, designed to interact with human tissue, respond to stimuli, even simulate muscle contraction. The aim isn’t just seamless control — it’s shared feeling.

Imagine a synthetic limb that doesn’t just grasp an object, but senses its weight, temperature, and texture — and transmits that data back to your nervous system. You wouldn’t just be commanding it. You’d be experiencing the world through it.

When the artificial becomes sensory, the division between body and tool collapses. You don’t just use the system. You become it.

And then what? If you feel through it, move through it, and interface with others through it… is it still separate from you?

. . . . .

The shifting shape of agency

This isn’t just about robotics. It’s about what kind of system we’re creating when humans and machines blend so tightly that the old boundaries stop making sense.

“We are, quite literally, cyborgs: biological brains augmented by social and technological scaffolding.”

— Andy Clark, cognitive scientist

Because the question isn’t “Will AI replace us?” That’s a decoy.

The real question is: What does it mean to be “us” in a system where tools think, limbs feel, and intelligence becomes modular?

We tend to think of AI as a competitor. But physical AI reframes it as a collaborator, a co-agent — one that shares in your decisions, your actions, your risks. The interface becomes the identity. And the architecture of the human — what it can do, where it ends — begins to stretch.

If you can wear six robotic arms and they respond to your thoughts — are they still tools? Or are they just you, extended?

And even if they are “you,” how much more input can the brain actually handle? Our minds evolved for two hands, one body. If we start layering on limbs, perspectives, and control interfaces, do we also need cognitive support — AI to help manage the complexity of our own expanded agency?

And if we’re sharing control with another intelligence, even a helpful one… is that still us?

This is the frontier we’re entering. Not a singularity. Not a takeover. But a slow, creeping redefinition of what it means to have a body… and to share it with machines.

Identity is no longer where the body stops. It’s where the network begins.

And as with all such shifts, it won’t begin with grand philosophical declarations. It will start with small things: an extra arm on a factory floor. A synthetic fingertip with nerve endings. A wearable interface that learns your movements better than you do.

And one day, without quite noticing, we’ll stop asking whether the machine is part of us — because the answer will already be obvious in how we move.

. . . . .

Sources & Further Exploration

Biohybrid Robotics

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666827021000014

Jizai Arms Video — University of Tokyo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZc_kcBddaI

MIT Supernumerary Robotic Limbs

https://robotics.mit.edu/project/supernumerary-robotic-limbs/

Nvidia CEO on Physical AI

https://brand-innovators.com/the-next-frontier-of-ai-is-physical-ai-nvidia-ceo/

Open Bionics Hero Arm

https://openbionics.com/hero-arm/

Embodied AI vs. Physical AI

https://medium.com/@thevalleylife/ai-terms-explained-embodied-ai-vs-physical-ai-2ad3bec23792

. . . . .