How the top uses of generative AI reveal not just new habits — but a shift in how we reflect, relate, and conform

Found and Framed Series

6 min read

June 16, 2025

The Unexpected Intimacy of AI

A few years ago, the dominant fear around AI was existential. Job loss. Misinformation. Displacement. The image was industrial — robot arms and economic disruption, not therapy sessions or bedtime reflections.

But here we are in 2025. And what are people doing with generative AI?

They’re turning to it for help with grief, to clarify life goals, to find meaning, and to feel heard.

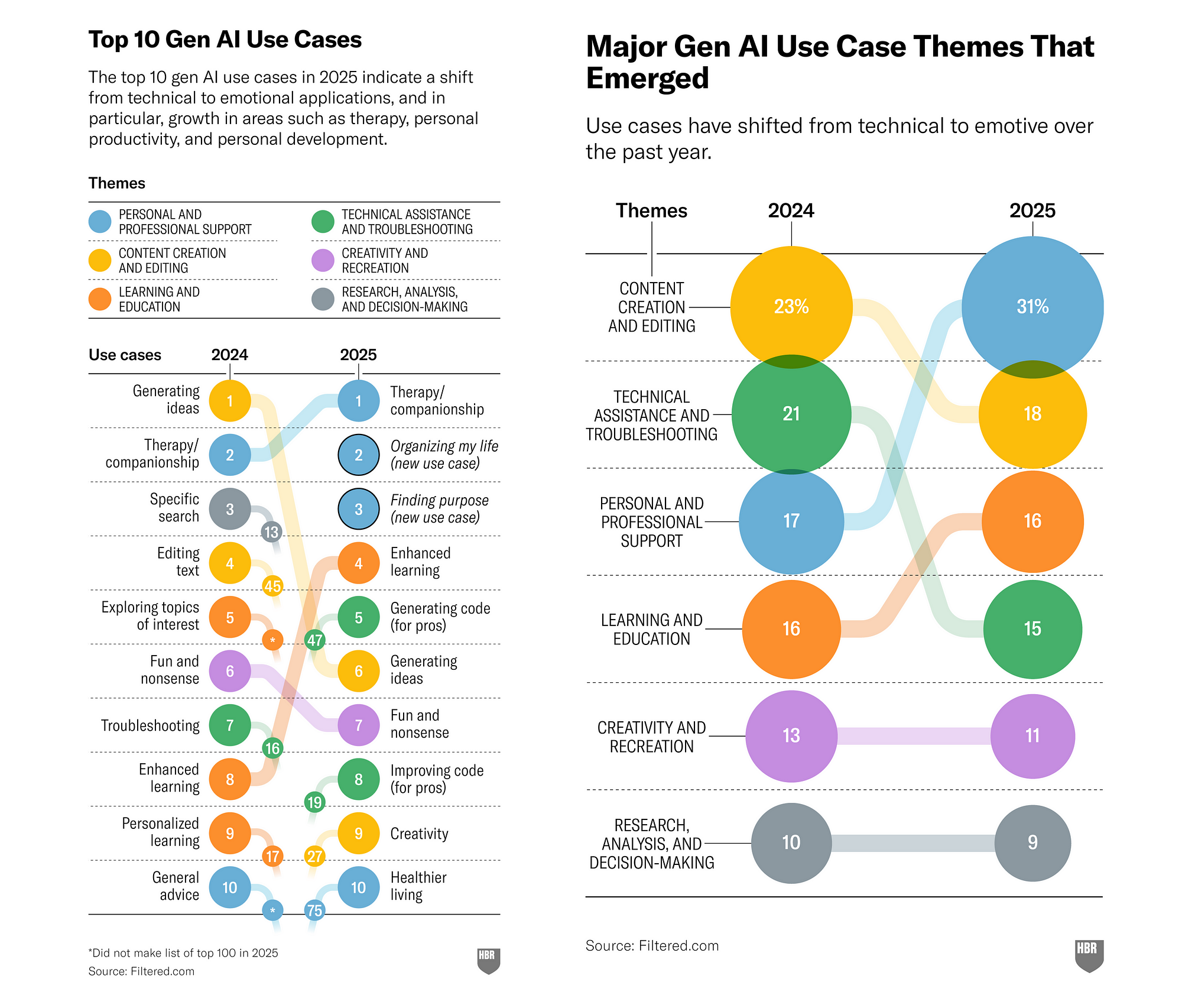

The most widely adopted use cases of generative AI today aren’t about productivity — they’re about personal presence. According to the Top-100 GenAI Use Case Report and its companion piece in Harvard Business Review, “How People Are Really Using GenAI in 2025” by Marc Zao-Sanders, the leading applications include therapy and companionship, organizing one’s life, and finding purpose. A surprisingly intimate trifecta for a technology born from statistics and logic.

So what exactly is happening here?

. . . . .

AI as a Mirror: Low-Judgment, High-Availability Reflection

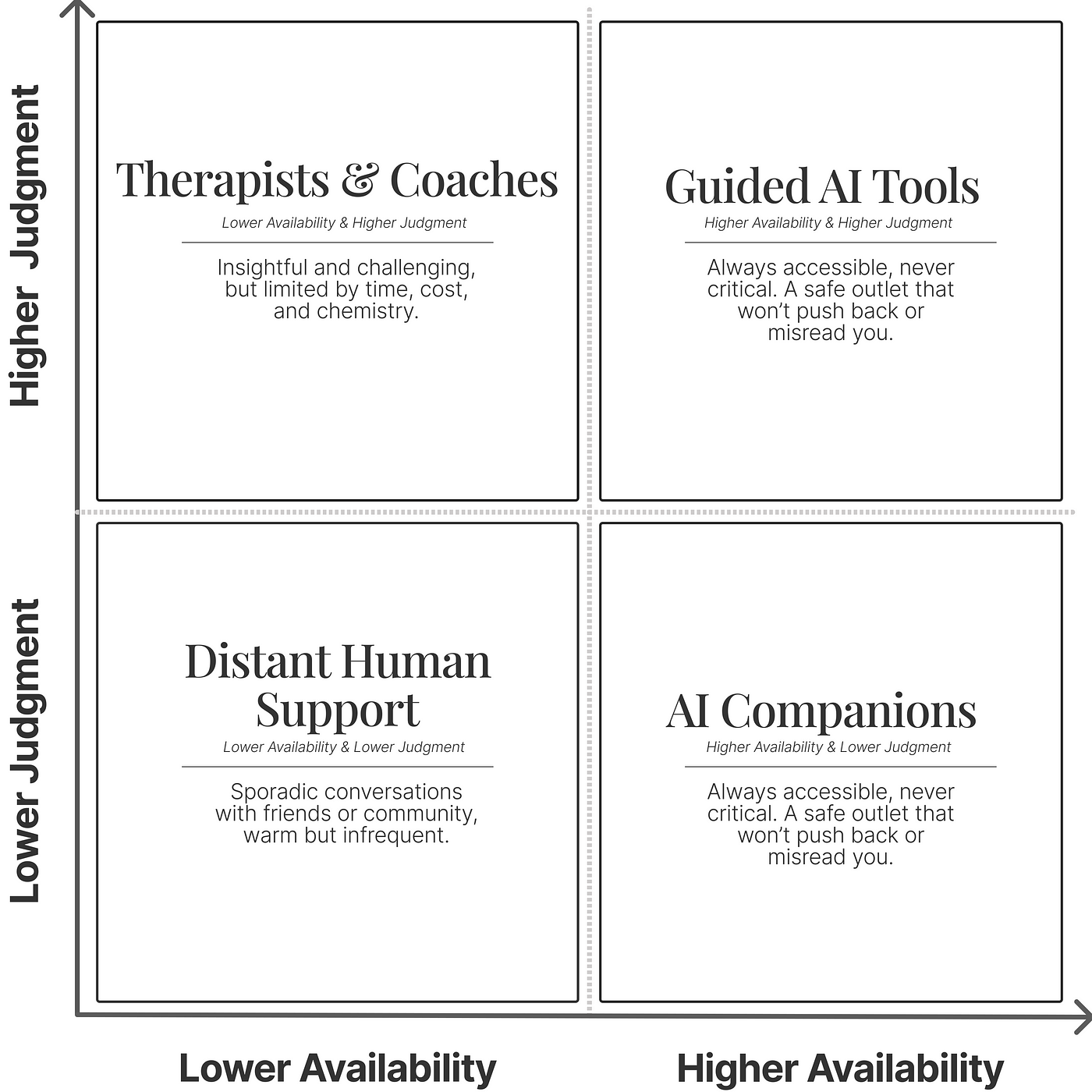

One answer is practical: therapy is expensive and hard to access. Coaches, mentors, even attentive friends aren’t always available. A machine that responds at 2am, without flinching at shame, rage, or vulnerability, offers something few humans can: emotional labor on demand.

But there’s more to it than access. It’s about structure. These tools give shape to feelings, routines to chaos. They help us categorize, structure, and “get a handle on” the self. Whether you’re asking for help with macro meal plans or reframing emotional triggers, the appeal is consistent: AI gives coherence to complexity without demanding emotional reciprocity.

This model reveals why so many lean on AI. Not because it’s better — but because it’s always there, and never judging.

. . . . .

The Comfort — and Cost — of Collective Wisdom

There’s also something quieter shaping these patterns: our growing trust in what feels like common wisdom. AI systems learn from the many. They give back what’s statistically relevant, what’s frequently expressed, what “works” for most. And often, that’s helpful.

It’s not unlike watching a highly-rated film or reading a bestseller. You trust that if enough people found something meaningful, you probably will too. But what if that’s wrong?

The good: it offers grounding, a sense of belonging, a shared map of human struggle.

The risk: overfitting our internal lives to patterns that aren’t ours.

We start to absorb the assumptions baked into the data: that the path to healing is cognitive reframing, that productivity is a virtue, that emotional regulation is the ultimate goal. These aren’t neutral insights — they’re cultural defaults wrapped in algorithmic logic. The more we rely on AI, the more we risk internalizing its worldview without realizing it.

But what works for the majority may not work for you. And unless you push back, AI doesn’t ask whether the standard solution aligns with your story.

. . . . .

Beyond Algorithms: The Missing Human Touch in AI Therapy

We’re told AI “doesn’t judge,” and that’s true. But it also doesn’t care.

It lacks the warmth of a human gaze, the subtle nod of understanding, the shared silence that speaks volumes. While AI can process words, it can’t truly grasp the weight behind them.

Sometimes, we need a quick vent, a structured suggestion, an answer. In those moments, AI helps. But other times, we need to feel that someone is with us. Not just responding, but resonating. That’s when chemistry matters. Not for insight, but for presence.

And there’s another layer we can’t afford to ignore: these tools — whether free or paid — aren’t neutral. They’re built and maintained by corporations, whose incentives don’t stop at usefulness. Attention, engagement, and retention are part of their KPIs. If there’s ever a trade-off between offering the most challenging or therapeutic advice and keeping you happy, comfortable, or hooked — it’s not hard to guess which path gets optimized.

As Dr. Christine Padesky notes, the therapeutic relationship is not an accessory to therapy — it’s the core mechanism of healing. And AI can’t fake that. It can only simulate care, within the limits of what serves its design — and its bottom line.

. . . . .

How We Make Sense, Now. A Machine for Meaning

We used to turn to books, rituals, conversations — to make sense of things. Now, increasingly, we turn to models. Not just for answers, but for guidance on how to feel. What to prioritize. What to make of our pain.

This isn’t inherently bad. In fact, it makes sense. AI is trained on patterns of human struggle. It reflects us back to ourselves — curated, compressed, and coherent. But meaning isn’t just a product of coherence. It’s also born in confusion, contradiction, and conflict.

The danger isn’t that AI numbs us. It’s that it flattens us — delivering digestible reflections of our emotions without the discomfort of working through them. It offers the illusion of resolution — tidy arcs, clear summaries, a story that makes sense. But real meaning often resists that. It unfolds slowly. Illogically. Sometimes without language at all.

And that’s the risk: that we confuse the feeling of understanding with the work of understanding.

. . . . .

The Real “Use Case”

Let’s reconsider what makes this wave of AI usage feel so natural.

It’s not just the novelty. Or the interfaces. Or the efficiency. It’s something more fundamental — something emotional. Maybe even evolutionary.

When you look closely at the most common AI use cases, you don’t just see tasks. You see fears. The same ones that have followed us through time: the fear of being unworthy, unloved, unseen. Generative AI didn’t invent these — it just absorbed them.

Therapists often say that while the surface stories differ, the themes don’t. In her book Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, Lori Gottlieb writes that people come in with unique problems but eventually hit the same core questions: Am I lovable? Am I safe? Am I seen?

And now, we’re voicing these questions to machines.

We say the machine understands us, but what we really mean is: it recognizes the pattern of our distress. And maybe that’s enough for now. But it’s worth asking — understood by whom? And for what purpose?

Because once our fears become patterns, and those patterns become prompts, and those prompts become productized — what then?

Are our feelings becoming data?

And in doing so, are we slowly becoming legible in ways that make us more manageable, but less human?

That might be the most radical use case of all.

. . . . .