Let’s stop chasing machines in our image — and start building machines that surpass our limitations.

Opinionated but Open Series

9 min read

June 2, 2025

From Fantasy to Friction

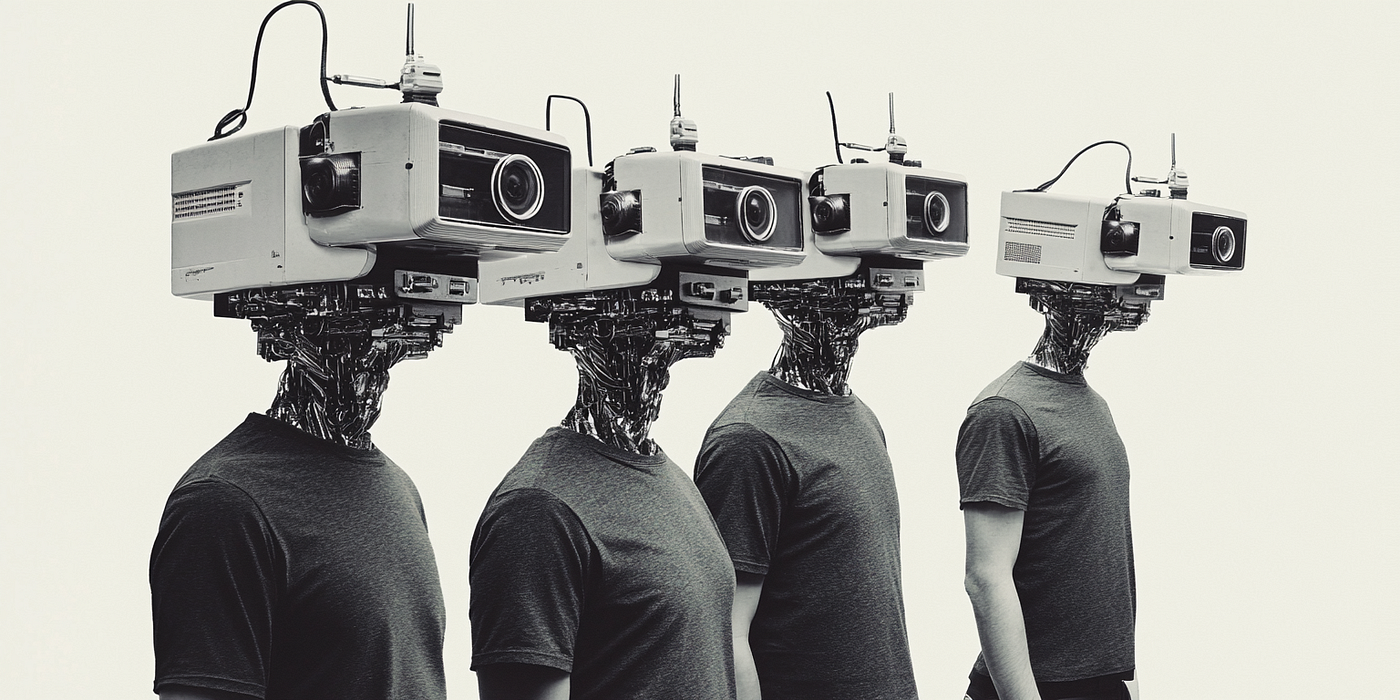

From sci-fi fantasies to tech expos, the vision of humanoid robots has captivated imaginations for decades. We picture them walking, talking, even empathizing — metal mirrors of ourselves. Yet, for all the hype, humanoid robots remain largely impractical, expensive, and inefficient.

Why, then, are we still chasing this anthropomorphic ideal? If our goal is to build machines that enhance human life, why are we trying to make them in our image?

The Case for Form Following Function

Designing a humanoid robot is like engineering a fish to climb a tree. The human body, as remarkable as it is, is not optimized for all environments or tasks. Walking upright, balancing on two legs, and manipulating objects with fingers are extraordinarily complex functions to replicate. They require advanced engineering, massive processing power, and intricate motor coordination.

And even when all this is achieved, the result is often underwhelming: fragile machines that fall over, struggle with basic tasks, and cost a fortune to build and maintain.

I don’t question that we’ll eventually get there — designing and building a fully functioning humanoid robot is likely just a matter of time. But the question isn’t if we can. The question is: why? And that’s something we might only be able to answer when that time comes.

“The right way to think about robots is not to model them after people, but to model them after the tasks they need to do.”

— Rodney Brooks, co-founder of iRobot and former director of MIT’s CSAIL

The logic behind humanoid robots rests on the assumption that our body is the universal interface. Yet this thinking is rooted in legacy bias — mistaking familiarity for fitness. We assume that because our form works for us, it must also be the most efficient form for machines. But what’s familiar isn’t always what’s optimal. True progress demands a departure from mimicry. The most effective robots don’t resemble us at all; they’re shaped by the demands of their tasks.

Designed for Purpose, Not Imitation

If we strip away the obsession with resemblance, what we see across the most effective robots is a different organizing principle: task-specific embodiment. These machines are not modeled on humans — they are modeled on purpose.

1. Purpose: What is it for?

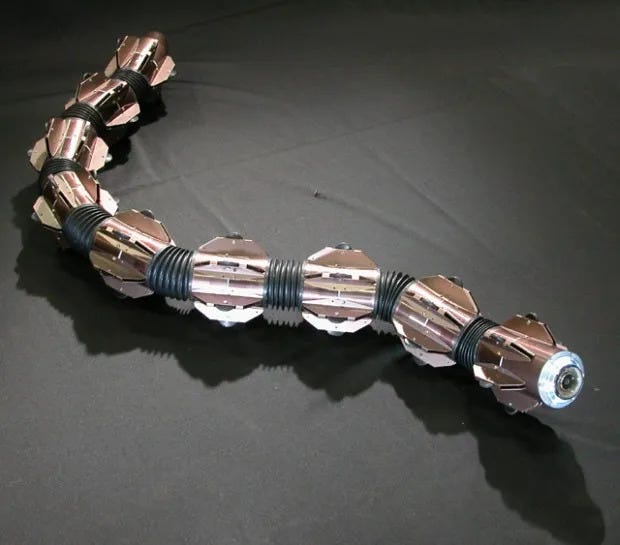

Start with function and everything else flows. The snake robot from Hirose-Fukushima Lab isn’t interested in bipedal elegance — it slithers into disaster zones where no human or wheeled machine could. Stanford’s Vinebot doesn’t walk, roll, or fly. It grows. A robot designed to reach through cluttered, chaotic space doesn’t need legs — it needs direction and expansion.

Rotunbot patrols streets and shallows for law enforcement, balancing like a gyroscope. evoBOT lifts and hauls cargo with skeletal efficiency — just limbs, no torso, no pretense. Proxie moves trolleys in complex facilities with quiet, utilitarian repetition. No faces. No chatter. Just outcome.

The purpose of each machine is its blueprint. No narrative, no nostalgia — just design shaped by what must be done.

2. Scale: From Microscopic to Modular

Not all robots are room-sized. Some are smaller than a grain of sand. Northwestern’s microscopic crab robot walks through tissue to deliver precision treatment. MIT’s ingestible robotic pill moves through the digestive tract like a scout. USC’s soft, light-powered bots can walk, carry, even dance — on the surface of water.

At the other end of the spectrum are modular robotic systems like MIT’s M-Blocks, which magnetically snap, stack, and roll into new forms depending on the task. These aren’t multi-purpose robots — they’re many-purpose machines.

Scale, in robotics, isn’t about taking up more or less space — it’s about redefining boundaries. Some solve problems by shrinking into places we can’t reach. Others adapt their very shape to meet changing environments. In both cases, scale becomes a form of strategy.

3. Power: How are they activated?

Forget cords and combustion. These robots are powered by light, muscle, pressurized air, chemical propulsion, even biological tissue.

At the edge of biotech, researchers from the University of Vermont and Tufts University, in collaboration with the Wyss Institute at Harvard, have built Xenobots — the world’s first “living robots” made from frog cells. These lab-grown organisms aren’t just alive in name — they crawl, self-heal, and even exhibit collective behavior.

Others, like the softbot swimmers from USC, respond to photonic signals to move, twisting and flexing in response to light instead of commands.

Form doesn’t drive function — energy does. And the more inventive we get with power, the stranger and more elegant these designs become.

A robot’s energy source isn’t just fuel — it’s a constraint, a behavior pattern, and a design logic all in one.

4. Intelligence: Where does the brain live?

Some of these machines are brilliant on the inside — onboard AI guiding every limb. Others rely on external control, swarm logic, or shared cloud intelligence to make decisions.

What matters is not where the “mind” resides — but how the robot adapts. Can it reroute? Recalculate? Learn?

Take ABB’s GoFa™ robotic arm, which learns through human demonstration and adapts its motion in real time on factory floors. Or the Xenobots, developed by Tufts University and the University of Vermont, which respond to biological cues without any centralized processor — blurring the line between reaction and computation.

These machines are not intelligent because they look like us.

They’re intelligent because they are designed to sense, decide, and act.

These robots don’t want to walk, talk, or wave.

They want to work.

And when you look at them closely, you realize:

They’re not a reflection of us.

They’re a reflection of what the problem demanded and the purpose they are created for.

. . . . .

The World Is Not Built for Them. It’s Built Like Us.

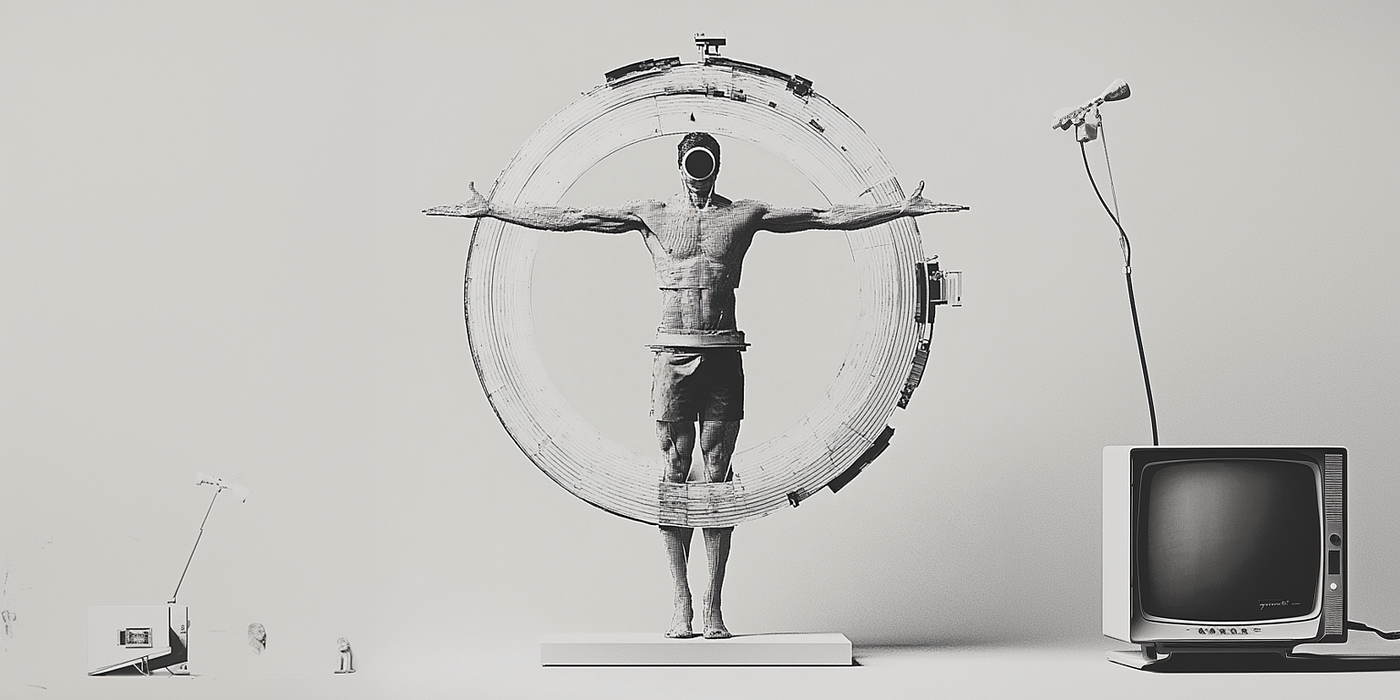

It’s not just that robots should serve us — it’s that the world they must operate in is shaped by our scale. Cities, doorways, utensils, factories, streets, furniture — all echo human proportions. A security robot in an airport isn’t the height it is for visibility — it’s because surveillance cameras, facial recognition systems, and signage are already positioned at human eye level. Its height mirrors our infrastructure, not its own optimal design.

Likewise, indoor delivery bots often move at a low, narrow profile — not because it’s ideal for robotic locomotion, but because they’re navigating corridors, turning through doors, and gliding past furniture — spaces all calibrated to human use.

A robot barista needs to reach a countertop, because that countertop was designed for our arms. Our built environment is a fingerprint of our bodies.

In this context, the appeal of humanoid robots becomes clearer. They don’t just resemble us for aesthetic reasons — they inherit a kind of architectural compatibility. Building a robot that fits where we fit is sometimes simpler than rebuilding the world around them.

Perhaps that’s the gap humanoids are trying to fill — not to outperform us, but to optimize us for the world we’ve already built. And maybe that’s why some believe humanoids, like Tesla’s Optimus, are being underestimated.

“People will underestimate Optimus just as they underestimated the iPhone.”

— Elon Musk, Tesla AI Day 2022

. . . . .

The Familiar Face: Why Emotion Matters

Humans are wired to read faces, even where none exist. That’s why we see smiles in clouds and fear in dolls. It’s also why humanoid robots can trigger emotional responses — comfort, curiosity, trust — but also unease. What begins as cute quickly shifts into creepy when behavior and appearance don’t align. It’s called the uncanny valley, and it lives at the edge of our empathy.

“61% of people say they feel more comfortable interacting with a humanoid robot than a machine with no human features.”

— IEEE Spectrum survey, 2023

There’s a spectrum here: familiar → endearing → uncanny → deceptive. As robots become more expressive, even more lifelike, we don’t just respond to them — we start projecting meaning onto them. That’s powerful in healthcare or education. But it’s dangerous when emotion masks capability, when users assume empathy or understanding where none exists.

Designers must not just ask: Will people like it? But: Will people be misled by it?

. . . . .

Machines of the Past: From Automata to Algorithms

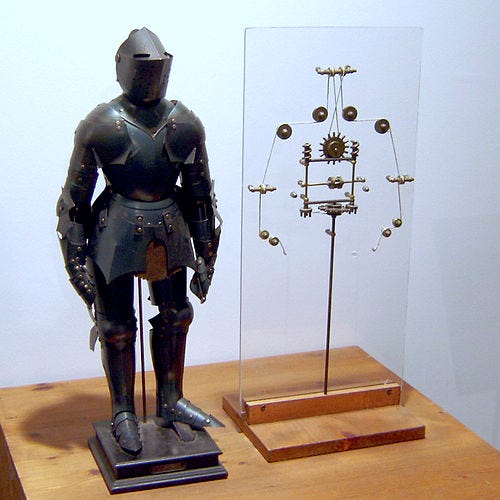

Our desire to create machines in our image is older than electricity. Da Vinci’s mechanical knight mimicked human motion for spectacle. Vaucanson’s duck digested food to provoke wonder. These automata didn’t adapt. They didn’t think. But they proved that imitation, even illusion, could captivate minds.

Today’s robots go further: they don’t just perform — they respond. We are no longer building wind-up curiosities — we’re designing systems that perceive context, process unpredictability, and act accordingly. That’s a profound leap: from automation to adaptive autonomy.

It’s no longer just about what a robot does. It’s about whether it understands why it’s doing it — and whether we trust that understanding.

. . . . .

Beyond Imitation: A New Robotic Imagination

The word “robot” was introduced in Karel Čapek’s 1920 play R.U.R., where robots were artificial laborers built in human form. But today, a robot is anything that senses, processes, and acts — whether physical or digital. Yet we still cling to the idea that it needs a face, arms, or a body.

Maybe it’s nostalgia. Maybe it’s legacy. But in doing so, we’re holding back entire design paradigms from evolving beyond our own biology.

“Humanoid robots are a distraction. The real work is being done in factories, hospitals, and farms with machines that don’t look like humans at all.”

— Gill Pratt, CEO of Toyota Research Institute

The future of robotics won’t walk on two legs. It will grow, slither, dive, fold, regenerate, replicate. It won’t remind us of ourselves — it will remind us of what’s possible.

Because the real limit on what robots can be is not mechanical. It’s conceptual.

We don’t lack the technology.

We lack the imagination to design beyond our own reflection. Can GenAI change that?

The next generation of machines isn’t coming to imitate us.

It’s coming to liberate us from the need to.

. . . . .

Sources & References

- Hirose-Fukushima Snake Robot — Tokyo Institute of Technology

https://www.me.titech.ac.jp/hirosegroup/snake.html - Stanford Vinebot — Growing robot for navigation in constrained spaces

https://news.stanford.edu/2017/07/19/plant-inspired-robot-navigates-growth/ - Rotunbot by Logon Technology — Amphibious robot for urban law enforcement

https://www.logontech.com/robotics/rotunbot (link may be illustrative; adjust if needed) - evoBOT by Fraunhofer IML — Dynamic bimanual transport robot

https://www.iml.fraunhofer.de/en/fields_of_activity/robotics/evobot.html - Proxie by Cobot — Autonomous indoor trolley robot

https://www.cobot.co.jp/en/products/proxie - Northwestern University Crab Robot — World’s smallest walking robot

https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2022/05/tiny-robotic-crab-is-smallest-ever-remote-controlled-walking-robot/ - MIT Robotic Pill — Ingestible medical robots

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/24/science/tiny-robot-medical.html - USC Light-Powered Robots — Water-walking softbots

https://techcrunch.com/2020/12/09/tiny-water-based-robot-is-powered-by-light-and-can-walk-move-cargo-and-even-dance/ - Living Robots from Muscle Tissue — Lab-grown biohybrid robots

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adt5888 - Modular Robots by Nicholas Nouri — Dynamic configuration robotics

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/nicholasnouri_innovation-sustainability-techforgood-activity-7177635953539211264-yM5J/ - Elon Musk on Optimus — Tesla AI Day (2022)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ODSJsviD_SU - IEEE Spectrum Survey — Public comfort with humanoid robots

https://spectrum.ieee.org/public-attitudes-robots-survey - Gill Pratt Quote — Toyota Research Institute

Referenced widely in media interviews and TRI events

(No single-source citation; paraphrased from public statements) - Rodney Brooks Quote — From talks and interviews

https://www.technologyreview.com/2017/11/13/148033/rodney-brooks-these-are-the-robotics-breakthroughs-youll-see-next/ - Da Vinci’s Mechanical Knight — Early humanoid robot concept

https://www.leonardodavinci.net/leonardos-robot.jsp - Vaucanson’s Digesting Duck — 18th-century automaton

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/12/the-canine-automaton-that-made-frenchmen-gasp/249091/ - Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. — Origin of the word “robot”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R.U.R.

. . . . .