A quiet gesture from Earth, drifting endlessly in the hope that someone, someday, might listen.

5 min read

May 14, 2025

Ona quiet morning in September 1977, a spacecraft lifted off from Cape Canaveral. Its name was Voyager 1, and onboard it carried something extraordinary: a golden phonograph record etched with sounds, images, and greetings from Earth.

It was never meant for us. It was meant for someone — or something — we may never meet.

The Golden Record wasn’t a beacon, exactly. It was a gesture. A snapshot of who we were at a particular moment in time, sent sailing into the cosmic dark. If it’s ever found, it will be by a lifeform that likely doesn’t look like us, think like us, or even experience time in the way we do.

And yet, we said hello.

. . . . .

The Universal Language of Hydrogen

Communicating with an alien species comes with some obvious complications. We can’t assume shared language, culture, or biology. So NASA’s engineers started with what they believed was the one universal constant: hydrogen.

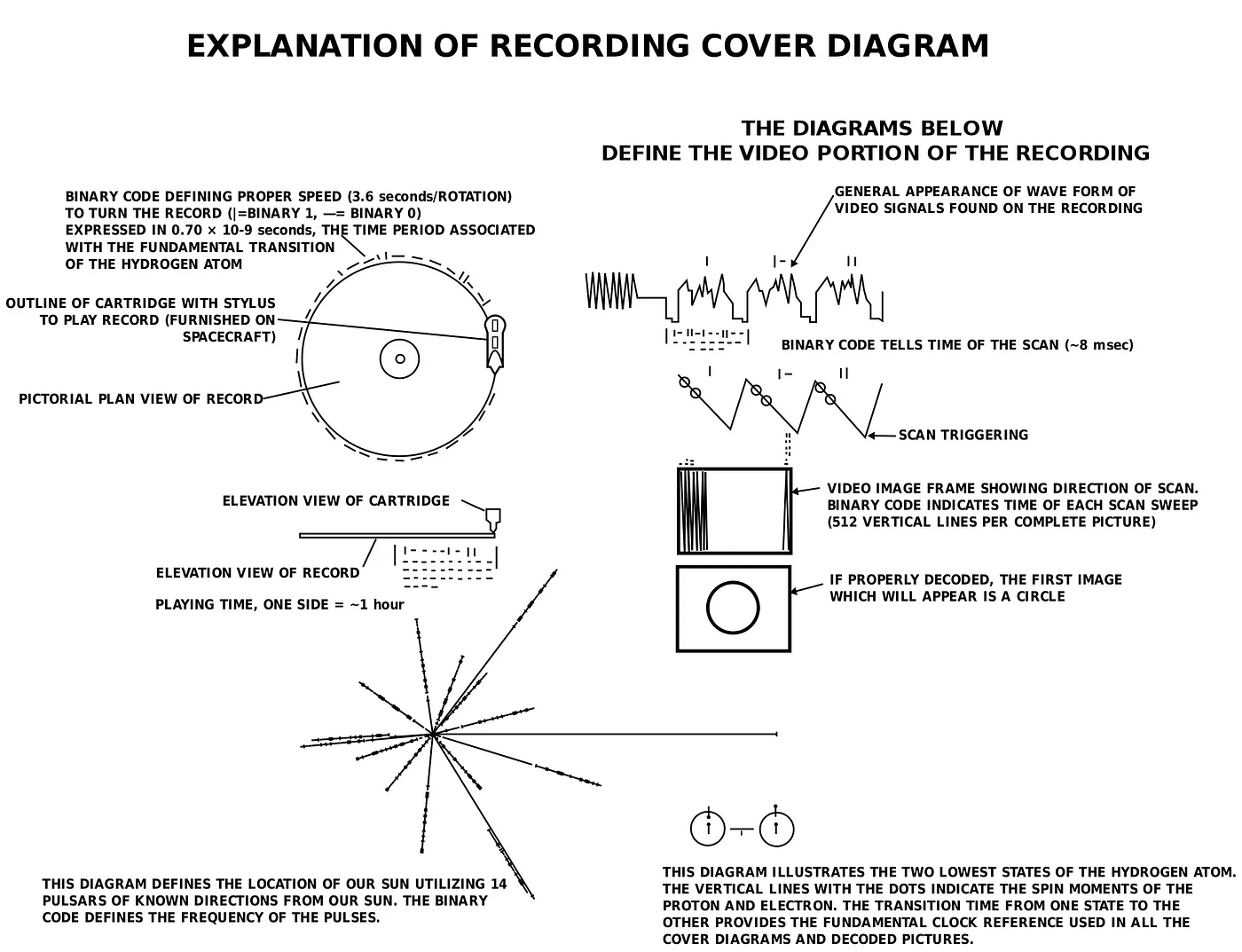

On the cover of the record is a diagram representing the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen — a fundamental property of the most abundant molecule in the universe. When the spins of hydrogen’s proton and electron realign, they emit a radio wave with a frequency of 1,420 MHz. Any scientifically advanced civilization might recognize this.

This frequency becomes the unit of measurement for everything else on the record: time, size, speed. It’s a way of establishing a shared frame of reference before introducing anything more complex.

“The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

— Carl Sagan, Chair of the Golden Record Committee

How to Play a Record in Deep Space

Knowing aliens wouldn’t have a phonograph player lying around, NASA included a stylus and cartridge, along with binary instructions etched directly onto the record’s cover.

The instructions explain how to play the record and at what speed — about 3.6 seconds per rotation, based on the hydrogen timing scale. If decoded correctly, the record begins with 55 spoken greetings in human languages, from Akkadian to Wu Chinese.

“Hello from the children of planet Earth,” one voice says.

What follows is a curated soundscape of life on Earth: birdsong, thunder, laughter, footsteps, a heartbeat, a kiss. Then music — 90 minutes of it — ranging from Bach and Beethoven to Senegalese percussion and Blind Willie Johnson’s blues guitar.

It wasn’t designed to impress. It was designed to represent.

Earth in 116 Images

The record also contains 116 images, encoded as analog signals that can be reconstructed frame by frame.

Some are scientific: DNA structures, mathematical constants, chemical diagrams. Others are simple and intimate — humans eating, a mother nursing her baby, a violin being played, a supermarket aisle, a gymnast in mid-air.

To make the decoding easier, the first image is a calibration pattern: a circle and a grid. If an alien observer can reconstruct that accurately, the rest of the visuals should fall into place.

These images are not just data. They’re fragments of how we saw ourselves and our world in 1977 — both ordinary and profound.

. . . . .

A Legacy Measured in Light-Years

As of April 2024, Voyager 1 is more than 14.8 billion miles from Earth, making it the farthest human-made object in existence (NASA JPL). It crossed into interstellar space in 2012, beyond the reach of the Sun’s influence.

Its twin, Voyager 2, travels a different path. Both carry identical golden records, each one drifting through the Milky Way — unpowered, silent, and still holding their message.

The records were built to survive for a billion years, far longer than any language, monument, or species we’ve ever known. Whether they’ll be found is uncertain. But they exist. They’re out there.

. . . . .

A Question That Still Echoes

Carl Sagan believed the act of sending the Golden Record was itself a kind of hope. Even if it was never played, it mattered that we had chosen to speak.

But the question remains:

How do we communicate with an intelligence we’ve never met?

Can understanding ever cross the vast distances between biology, cognition, and time?

As we increasingly create intelligence of our own — machine learning, generative AI, and language models trained on the echoes of our thought — this isn’t just a question about aliens. It’s about us.

Who are we trying to reach? And when we send messages into the void, are we truly understood?

. . . . .

References & Further Exploration

- NASA Voyager Mission: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov

- Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record, Carl Sagan et al. (Random House, 1978)

- Golden Record Image: Wikimedia Commons

https://science.nasa.gov/gallery/images-on-the-golden-record/